Humans love collecting stuff – we always have. From the hunter-gatherer tribes of the Paleolithic era who foraged and stored surplus food, to modern-day art collectors and shopaholics – people like to accumulate possessions.

When does a love of collecting tip the scales though? Collectors tend to take pride in displaying and caring for carefully selected items. Hoarders are more likely to stockpile possessions indiscriminately – and hide their behaviour from others.

People hoard inanimate objects (such as clothes or magazines) as well as animate objects (such as adopting multiple pets).

When the sheer amount of objects you’ve collected create unsanitary living conditions, or you’ve unable to adequately care for all of your animals, help for compulsive hoarding may be in order.

Compulsive hoarding affects approximately 4 to 6% of the population, and it’s a serious risk to safety. A recent report by the Melbourne Metropolitan Fire Brigade demonstrated that of all fire-related deaths over the decade to 2009, 24% were attributable to hazardous hoarding conditions in the home.

Are your spending and collecting habits overtaking your living environment?

Do you feel overwhelmed and distressed about the thought of organising or discarding those items?

Specialist anxiety counselling can help you take control of your hoarding behaviour, and re-organise your home space so that it’s a safe and comforting place to live.

Compulsive Hoarding Signs

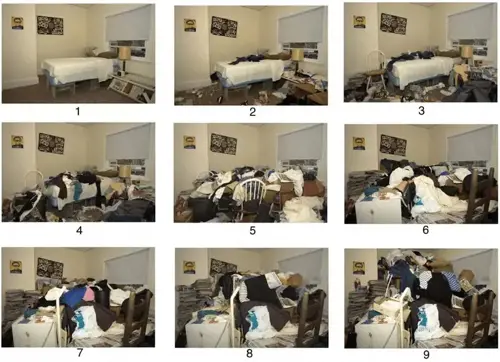

Research has identified 9 levels of hoarding which range from sanitary living conditions and habitual messiness, to severe squalor that poses a risk to psychological wellbeing and physical safety.

Oxford University Press has developed a Clutter Index Rating test to check for compulsive hoarding signs– you can take it by clicking on the photo below:

- Clutter Image Rating Tool (interactive). Copyright: Oxford University Press.

In addition to the obvious visual signs of clutter in an environment, the following symptoms are some key indicators of issues with compulsive acquisition and saving behaviour:

- Social isolation: feeling embarrassed or ashamed about inviting friends or family over due to the state of your living space

- Extreme pleasure when acquiring new items

- Emotional distress and anxiety at the thought of discarding items or re-homing pets

- Feeling overwhelmed by your clutter and the thought of organising it

- Unable to use rooms as they were intended (such as the kitchen or bathroom) due to build-up of possessions

- Saving multiples of items that ‘might be useful’ one day

- Financial and relationship difficulties that stem from compulsive spending

What causes hoarding?

Although the causes of compulsive hoarding are unknown, there are a number of risk factors associated with hoarding disorder. These include diagnoses of anxiety, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and exposure to significant trauma.

Compulsive hoarding has long been identified as one of the symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Yet over the past 15 years, neuroscientific research has determined that hoarding and OCD are genetically distinct mental health issues*. This discovery has lead to compulsive hoarding’s classification as a separate mental health disorder in 2013’s DSM-V.

* This may also be why treatment for hoarding pre-1990 had such a low success rate – specialist OCD counselling failed to address the unique characteristics and underlying causes of hoarding.

The genetic component of hoarding disorder is important, and may account for at least 50% of the variance in compulsive hoarding. Having a parent or sibling with hoarding behaviours significantly increases the likelihood of someone developing a hoarding disorder.

Compulsive hoarding: Age of onset

Although compulsive hoarding was once considered to be the domain of wealthy eccentrics, such as the hermit hoarder Collyer brothers of Harlem, or mother and daughter Big Edie and Little Edie Bouvier Beale of Grey Gardens fame, anyone can be affected by hoarding impulses. Compulsive hoarding may develop in childhood, adolescence, or much later in life.

The average age of someone diagnosed with hoarding disorder is 50. Hoarding is far more prevalent amongst older people who have accumulated a lifetime of possessions. Many elderly people have a strong emotional attachment to their possessions, and due to social isolation may not have family or friends around to help them deal with a house full of clutter.

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy: Effective treatment for compulsive hoarding

Recently there’s been a rise in popularity of the ‘de-cluttering’ movement. There are myriad self-help books available for people seeking to rid themselves of excess possessions, and pare down to the bare living essentials.

Yet the latest research suggests that simply clearing an environment of clutter or animals doesn’t address the underlying causes of compulsive hoarding. In fact, getting rid of clutter may elevate anxiety and distress levels, and increase future hoarding behaviours.

A 2015 meta-analysis examining the efficacy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT) as a treatment for compulsive hoarding reported that CBT significantly reduced the symptoms of hoarding disorder. Symptoms such as difficulty discarding items, clutter build-up and acquisition of new possessions responded well to CBT counselling, and in some cases those behaviours were resolved altogether.

How does CBT counselling for compulsive hoarding work?

Instead of prioritising de-cluttering improvements to the home environment, CBT focuses on addressing the underlying beliefs and emotions about possessions that lead to problematic acquisition and storage.

Counselling for compulsive hoarding includes the following CBT techniques:

- Maintaining a daily log of new acquisitions, to track triggers and identify patterns of collecting

- Challenging maladaptive beliefs about the value of hoarded items and increasing motivation to de-clutter

- Learning practical skills to address hoarding behaviours, such as decision-making and organisational techniques

- Reducing the hoarding impulse by addressing associated symptoms of anxiety, depression and substance use

- Using relaxation and mindfulness strategies to increase resistance to the acquisition of new items, and discover alternative sources of fulfilment and joy

Compulsive hoarding is a serious issue, but it can be addressed with specialist CBT counselling.

If you or someone you care about needs some support to overcome impulsive spending, compulsive acquisition or troublesome saving behaviours, talking to a professional can help you to clear the psychological clutter – and free yourself from the distress caused by compulsive hoarding.

Marcus Andrews

Marcus Andrews is the founder and director of Life Supports, which was established in 2002. He has extensive professional experience working as a counsellor and family therapist across a broad range of issues. The core component of his role at Life Supports involves the supervision of other counsellors, including secondary consultations. Marcus has worked in many sectors, including private, government, non-profit, health, forensic and community practice.

Recommended Reading

Get help now

Appointments currently available

Open 8am to 8pm weekdays and 9am to 5:30pm weekends